Remember how your body reacted to that first-ever inhaled puff, dip or chew of tobacco? Although some took to smoking like ants to sugar, what most recall is how utterly horrible it tasted.

You may have felt dizzy, nauseous or if like me, your face cycled through six shades of green. My mouth was filled with a terrible taste, my throat on fire, and my lungs in full rebellion as scores of powerful toxins assaulted, inflamed, and numbed all tissues touched.

Prior to that moment, you may have heard that tobacco can be addictive. Vaping e-cigs aside, after such an unpleasant introduction, you were convinced that it couldn't possibly happen to you. How could it? If like most, you didn't like what just happened. How could you possibly get hooked?

As strange as this may sound, even for e-cig users, like or dislike have little to do with chemical dependency.

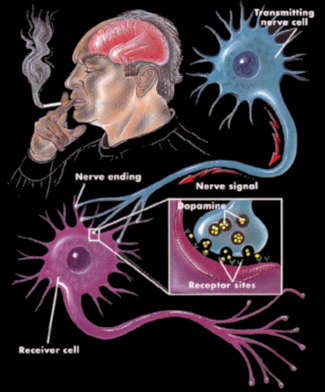

Whether your body rebelled or not, nicotine had activated our brain dopamine pathways, the mind's survival instincts teacher and motivator. The primary purpose of that brain circuitry is to make activating events extremely difficult to forget or ignore.

How do brain dopamine pathways teach and motivate action? Knowing will aid in understanding both how we became hooked and why breaking free appears vastly more daunting than it is.

Remember how you felt as a child when first praised by your parents or teachers for keeping your coloring between the lines or for spelling your name correctly? Remember the "aaah" satisfaction sensation? Remember that same feeling after making and bonding with a new friend? "Aaah!"

We had just sampled the mind's motivational reward for accomplishment and peer bonding. An earned burst of dopamine was followed by an "aaah" wanting satisfaction sensation. It caught our attention, alerted us to what was important, and created a memory of the event that would help establish future priorities.

Bursts of dopamine were also felt when we anticipated accomplishment, peer bonding, or other species survival activities. We were now being motivated and working to satisfy dopamine pathway wanting, the "aaah" relief sensation felt when anticipating or experiencing desire's satisfaction.

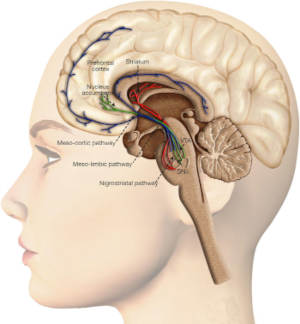

Our sense of wanting being satisfied is generated by the release of dopamine within multiple brain regions, primarily in our mid brain, inside cell structures known as the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the nucleus accumbens.[1]

Two different yet overlapping dopamine pathways are responsible for wanting and its satisfaction. Our "tonic," background or baseline dopamine level determines our level of wanting, if any. Our "phasic" level or bursts of dopamine generate the "aaah" sensations sensed as wanting is satisfied.

Generally, as our tonic or background dopamine level begins to decline we begin to experience wanting. As phasic burst releases occur, our tonic level is gradually replenished by burst overflow into our tonic pathway, and wanting subsides.[2] The word "tonic" means to restore normal tone.

Brain dopamine pathways were not engineered to act as wanting satisfaction brain candy. Satisfaction is earned. Both a carrot (phasic) and a stick (tonic), they are a preprogrammed and hard-wired survival tool that teaches and reinforces our basic survival instincts.

Dopamine pathways are present and strikingly similar in the brains of all animals. They originate in the deep inner primitive, compulsive region of the brain known as the limbic mind, and extend forward into the conscious, rational, thinking portion of the brain.

Pretend for a moment that you're extremely thirsty. Really thirsty! Can you sense "wanting" beginning to build? Now, imagine drinking a nice, cool glass of refreshing water. Did you notice the "wanting" subside, at least a little?

Compliance with wanting generates a noticeable "aaah" relief sensation. The greater our wanting, the more intense our "aaah."

Our dopamine pathways are the source of survival instinct anticipation, motivation, and reinforcement. Hard-wired instincts include eating food, drinking liquids, accomplishment, companionship, group acceptance, reproduction, and child-rearing.[3]

Our brain dopamine pathways cause our compliance with wanting to be recorded in high definition memory, in our forehead just above our eyes (our prefrontal cortex). It's what researchers call "salient" or "pay attention" memories.[4]

Although still poorly understood, the intensity of dopamine pathway wanting appears to stem from a combination of at least three factors. Those factors include a diminishing tonic dopamine level, the collective tease and influence of old wanting satisfaction memories, and self-induced anxiety if satisfaction is delayed.

The tease of thousands of old wanting satisfaction memories can be triggered by a physical bodily need, by subconscious conditioning, or by conscious fixation.

Once their collective influence is triggered, as though bombarded by a thousand points of light, we have no choice but to recall exactly what needs to be done in order to satisfy wanting.

If you felt any wanting or relief with our pretend water-drinking example, it was due to old thirst and replenishment memories, not a biological need.

Yes, our "pay attention" pathways are a built-in, circular, self-reinforcing survival training school.

Wanting is triggered by our tonic dopamine level declining in response to a need, conditioning or desire. Old wanting satisfaction memories fuel wanting by constantly reminding us of exactly what needs to be done to make it end. Anticipating satisfaction may generate additional anxieties which further inflame wanting.

Obedience releases a sudden phasic burst of dopamine. Wanting ends once our need, conditioning or desire is satisfied and our tonic dopamine level returns to normal. The release also creates a vivid new high definition memory of how wanting was satisfied.

So, how does all of this relate to nicotine addiction?

References:

2. Grieder TE et al, Phasic D1 and Tonic D2 dopamine receptor signaling double dissociate the motivational effects of acute nicotine and chronic nicotine withdrawal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Science U S A. 2012 Feb 21;109(8); pages 3101-3106. Epub 2012 Jan 20.

3. Stefano GB, et al, Nicotine, alcohol and cocaine coupling to reward processes via endogenous morphine signaling: the dopamine-morphine hypothesis, Medical Science Monitor, June 2007, Volume 13(6), Pages RA91-102.

4. Kathleen McGowan, Addiction: Pay Attention, Psychology Today Magazine, Nov/Dec 2004, an article reviewing the drug addiction research of Nora Volkow, Director of the National Institute of Drug Abuse; also see Jay TM, Dopamine: a potential substrate for synaptic plasticity and memory mechanisms, Progress in Neurobiology, April 2003, Volume 69(6), Pages 375-390.

All rights reserved

Published in the USA

Updated October 13, 2020 by John R. Polito